Wonderful Dogs

Our Best Friends!

Wonderful Dogs

Our Best Friends!

Dogs diverged from Gray Wolves Dogs diverged from Gray Wolves

|

They romp and cuddle and strut their stuff in an endless variety of antics, environments, and conditions. They sniff out danger, know when we’re sad, and learn tricks for treats and the joy of pleasing their people.

Wonder of wonders: The dog has the physical and mental characteristics of a top predator yet willingly adapts to human households in exchange for food, shelter, and companionship.

It’s a dream relationship: Capable of surviving on its own as a species, the dog – alias Canis lupus familiaris – nonetheless accepts human control in its life and responds with loyalty, courage, affection, a willingness to share home and hearth, and, in many cases, by working alongside his human benefactors.

We didn’t have to tame the dog; he tamed himself to co-exist with us. The canine saga crosses millennia; long before dogs became pampered pets, their affinity for a connection with people gradually formed an extraordinary partnership unequaled in human history: dogs found game so man could eat; guarded and herded flocks so shepherds could provide meat and wool and milk to their communities; served as sentries and protectors for royalty at home and in war; killed vermin to protect grain stores; drove cattle to market; and hauled goods in carts and on travois and sleds. Today, dogs use those same skills and work ethic in modern pursuits from tracking criminals and finding lost children to sniffing out bombs, serving handicapped owners, and participating in a variety of sports and games. As a bonus, the dog’s exceptional ability to form an emotional attachment with people enables it to provide comfort and bring joy to owners, their families, and members of the community.

The bond between man and dog is so extraordinary, so magnificent, that scientists have been trying for hundreds of years to unlock the mystery of its beginning. So far, geneticists, canine specialists, and archaeologists have compiled evidence that suggests dogs and gray wolves diverged from common wolf ancestors in Europe and Central Asia sometime between 40 thousand years and 27 thousand years ago, have a closer genetic relationship with ancient gray wolves than with the modern wolf species, and were part of human hunter-gatherer societies at least 12 thousand years ago. Dogs were definitely there when people began to abandon nomadic life, raise crops, domesticate sheep and goats, and settle in villages.

Dogs were already living with humans when they abandoned nomadic life! Dogs were already living with humans when they abandoned nomadic life!

|

Although the ubiquitous presence of dogs as household pets is a relatively recent phenomenon, there is a growing body of research to indicate that early societies throughout the world prized dogs as guardians, companions, hunting partners and even as gods and royalty. Historians and archaeologists have found evidence that dogs were highly regarded throughout ancient Mesopotamia (the Fertile Crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that today includes Iraq and parts of Iran, Syria, and Turkey) and in India, Greece, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica (now Mexico and Central America). Roman law mentions dogs as guardians of homes and flocks, Egyptian tomb paintings show dogs as royal guards and hunting companions. Socrates considered dogs to be true philosophers, and Plato called them “lovers of learning.” Although the Chinese and Mesoamericans had deep ties with their dogs and honored them as gifts from the gods, they also ate dog meat and at times considered them to be bad omens.

This affinity for life with humans made it inevitable that dogs would be front and center as humans made the transition from hunter-gatherer groups to agricultural societies: dogs herded and protected livestock, continued to aid hunters seeking game for food and skins, warned farmers of raiding parties, killed vermin that ate stored grain, hauled provisions, and even warmed beds on cold nights.

As the relationship grew, man took the existing types of dogs and refined them to create breeds with specific skills and adaptations. Although most breeds are but a few hundred years old, early artists, writers, and ancient records depict and describe dogs of types similar to the breeds of today.

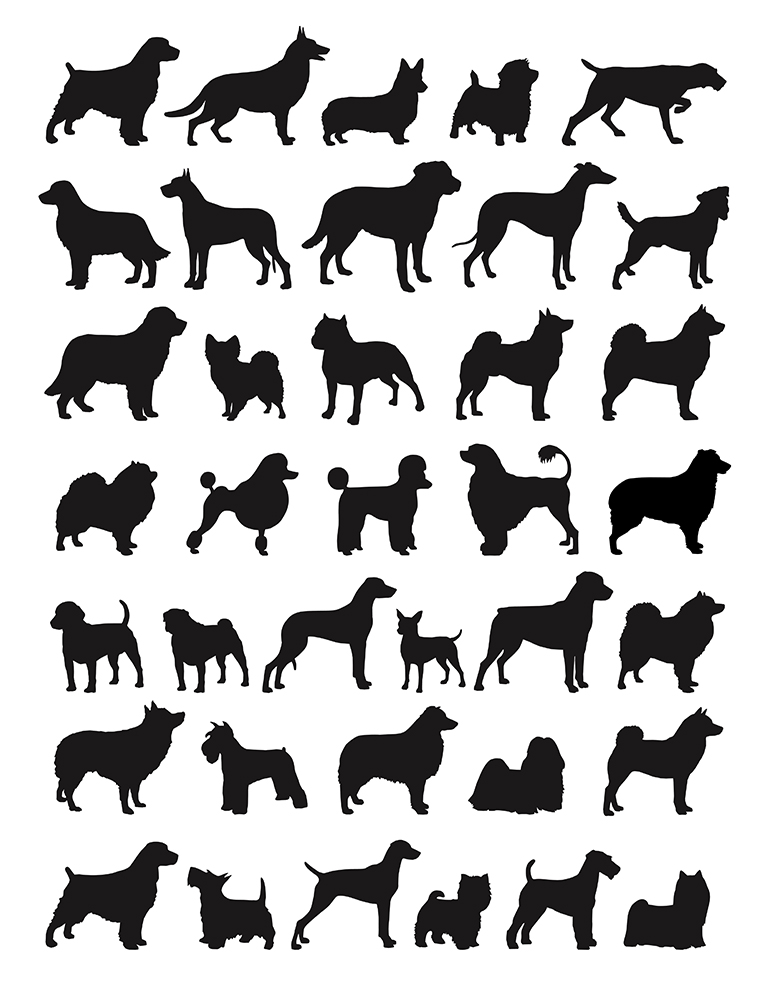

Nearly every region in the world has developed breeds of dogs -- dogs of all shapes and sizes and dispositions! Nearly every region in the world has developed breeds of dogs -- dogs of all shapes and sizes and dispositions!

|

The tasks for dogs are universal; just about every region of the world developed breeds to hunt, guard, herd, and provide power, but different breeders in different regions needed slightly different skills or physical adaptations to meet particular climates, terrain, ecosystems, local practices, or personal ideals. As a result, the hunting dogs developed to flush and retrieve upland game birds in thick underbrush differ in size and method of working from dogs that hunt in open fields and dogs that retrieve in water. In like manner, dogs that guard have different temperaments than dogs bred strictly for companionship, dogs that herd have different abilities than dogs that hunt by scent or sight, etc.

The development of dog breeds is a testament to the ingenuity of man and the adaptability and character of the dog. Without the knowledge of genetics we depend on today, early breeders nonetheless understood that dogs inherited temperament, coat, size, talent, and trainability from their sires and dams, and they selected dogs that met their needs to produce next generations.

So…

Those who needed dogs to herd sheep modified the predatory skills that are part of a dog’s mental wiring to come up with breeds such as Border Collies from the border country of England and Scotland, Rough and Smooth Collies from Scotland, Pulis from Hungary, and Buhunds from Norway that can gather and drive sheep – and along the way, they made possible the growth of the wool industry.

Shepherds who needed guard dogs to prevent predation on flocks used the territorial behaviors and courage of large dogs to create breeds such as the Great Pyrenees from the mountains of southwestern Europe, Maremmas from Italy, Kuvasz from Hungary, and others to protect them. Those who wanted dogs to protect cattle and drive them to market came up with the Rottweiler from Germany and the Bouvier des Flandres from Belgium.

Farmers who needed multi-purpose dogs that could herd, guard, and provide hauling power used the protective instincts, herding skills, and strength of the Rottweiler, the Briard from France, or the Greater Swiss Mountain Dog.

In like manner, hunters developed retrievers, setters, and spaniels to find, flush, and retrieve game birds and a variety of hounds to locate game animals by scent and sight. Depending on the tasks at hand, early breeders founded strong breeds to pull carts and drag fish nets; feisty terriers to keep homes, farms and businesses free of vermin; swift sighthounds to chase down large and small game; and jack-of-many-trades breeds that can herd, guard, and drive sheep or cattle; hunt rodents and other pests; pull a cart; and guard the home.

What is a breed?

A breed of dogs is one that has fixed characteristics and passes those characteristics to the next generation. The breed standard defines the structure, movement, color, size, and other traits; the breed club guards the written standard, sets ethical guidelines for breeders, and protects breed integrity; the breed registry keeps the records of all dogs bred and litters born.

Dog breeds spread throughout the world as people sent their armies to conquer new lands, expanded their settlements, and traveled abroad. Some breeds such as the mastiffs of Asia contributed new blood to local European dogs that led to the development of livestock guardian breeds in Italy, Turkey, Spain, and other countries and ultimately to many other breeds. Governments used favored breeds as diplomatic gifts, and travelers brought strange breeds home.

Many breeds carry the name of a country of origin (German Shorthaired Pointer, American Water Spaniel, etc.) or a region of development (Weimaraner, Shetland Sheepdog, etc.) France and Great Britain produced the largest numbers of breeds, followed by the US and Germany.

The American Kennel Club divides dog breeds into seven groups: Sporting (waterfowl and upland bird hunting dogs); Hound (breeds that hunt by scent or sight); Working (breeds that guard, pull, and do water rescue); Toy (breeds developed as pets, flea magnets, and bed warmers for royalty); Terrier (dogs bred to hunt rats, foxes, badgers and other pests); Non-sporting (a hodge-podge of breeds with a broad range of origins and purposes); and Herding (dogs bred to gather and drive cattle, sheep, and goats).

The groupings are loose, and there’s lots of crossover. Some terrier breeds are actually all-around farm dogs (Airedale, Soft-coated Wheaten, et al); some non-sporting breeds originated as hunting dogs (Poodle, Shiba Inu, et al), some working breeds (Samoyed, Rottweiler, et al) could find a home in the herding group, etc.

It is obvious to even a casual observer that many breeds look alike. Some seem to differ only in size (i.e., the tiny Italian Greyhound, medium-size Whippet, and large-sized Greyhound) or coat color or type (i.e., the four Belgian sheep herding breeds). The similarities occur when people in different regions develop breeds for comparable purposes, climates, terrain, or habitats, keep accurate generational records, and follow a written standard.

The United Kennel Club also groups dogs by purpose but uses slightly different criteria. In UKC, the sighthounds are not included with the scenthounds but instead are paired with pariah dogs, a small group of dogs of a wild type that includes the Canaan Dog, Carolina Dog, and Thai Ridgeback.

Obviously, dogs come in many sizes and several coat types, but all have the same basic physical attributes: a predator’s eyes set in the front of the skull, teeth suitable for killing prey and chewing bone, intestinal systems suited for digesting raw meat, non-retractable claws, padded feet for running on rough ground, tails for balance in turning, and keen senses of hearing and smell.

Dogs see two colors (blue and green) and can differentiate objects based on brightness, but they are near-sighted and their vision is not as sharp as that of humans. Their noses make up for the lack, however; depending on the breed, a dog has 100-300 million scent receptors in its nasal cavity, as compared to about 10 million receptor cells for a human nose. As if this weren’t enough, about 40 percent of a dog’s brain is dedicated to discerning and identifying odors, and the specialized Jacobsen’s organ in the nasal cavity deepens the scenting ability even more.

Many breeds of dog retain the upright ear of their canine ancestors. Many breeds of dog retain the upright ear of their canine ancestors.

|

Dogs hear a broader range of sounds than people and have muscles that allow adjustment of their ear flaps or pinnae to target what they hear. These muscles allow the dog to redirect his ear canal, thus improving the collection of sounds.

Domestication and purpose-breeding changed the structure of the canine ear flap. While many breeds retain the upright ear of their canine ancestors, hounds and sporting breeds have floppy or pendulous ear flaps selected by breeders to protect the inner ear from debris when the dog hunts in rough terrain. There’s a downside to floppy ears, though; these dogs do not hear as well and may be more susceptible to ear infections.

Your dog may eat kibble, but their teeth are made for killing. Your dog may eat kibble, but their teeth are made for killing.

|

Canine dentition complements the dog’s acute senses of smell and hearing; all are suited for an animal that hunts for its dinner. The fact that we feed dogs out of a bag or can makes no difference; the dog still has canine teeth (fangs) for killing, incisors for tearing meat, sharp-edged premolars for shearing, and flattened molars for crushing bone.

Canine coats differ in color, pattern, texture, and thickness. Some breeds are just about hairless; others have thick double coats to protect them from harsh weather and other environmental conditions. Some breeds have a single or limited color or pattern; others have a broad spectrum of both. For example, Weimaraners are gray all over; Rottweilers are black with red markings on muzzle, chest, belly, and legs; and Canaan Dogs come in cream, red, brown, and black with or without white markings and with colored patches on a white background. Some breeds have elaborate patterns: Collies, Shetland Sheepdogs, Dachshunds, and Australian Shepherds come in a mottled pattern known as dapple in Dachshunds and merle in the others.

Double coats are soft underneath to protect skin from wet or cold conditions and harsh on top to keep rain and snow from getting to the softer undercoat. Double-coated dogs shed profusely at least once a year.

A Labrador Retriever -- pretty much what you were expecting. A Labrador Retriever -- pretty much what you were expecting.

|

Unlike cats, dogs come in many sizes and shapes. Unlike cat breeds, dog breeds are suited for a variety of tasks from herding and hunting to guarding and tracking. And unlike cats, dogs are eminently trainable, making them suitable as true companions, well-mannered household residents, and working partners.

The value of classifying dogs by breed lies not in a somewhat arbitrary group assignment but in the predictability of size, coat type, exercise needs, trainability, and some ingrained behavioral traits that go along with the breed’s original purpose. In other words, although few of their original jobs remain, modern dogs retain the physical and mental characteristics of their predecessors. Each breed’s DNA programs the dog’s size, coat type, energy level, trainability, grooming needs, athletic ability, attitude, and talents, so you can be pretty sure that surprises will be limited. For example, the Labrador Retriever – America’s most popular breed – is a 60-70-pound hunting dog with a short, insulating double coat and a talent for retrieving ducks. As a family pet, the Lab loves people, has a penchant for carrying objects in his mouth, requires grooming when shedding that short double coat, and needs exercise to keep him in shape and out of trouble. He easily masters the good manners necessary for family life but can be rowdy if untrained. While an active family with older children may find these traits acceptable, the Lab may not be a good choice for a quiet family or one without time and energy to do the necessary training.

It’s obvious that purebred dogs bring beauty and diversity to our lives, and should be equally as obvious that their particular characteristics can enhance or detract from those rewards. For example, Newfoundlands are friendly, laid-back dogs good with children and needing only moderate amounts of exercise, but they are also huge, expensive to feed, and slobbery, and they shed buckets of hair each year. So, a family living in an apartment or a single person who doesn’t like slobber on the furniture and walls should probably look elsewhere for a friendly, laid-back, moderately active family dog.

Prospective dog owners would also do well to go beyond the practical needs and consider their emotional needs when selecting a breed. For example, most sporting breeds are friendly and outgoing,most terriers are feisty, many herding and guardian breeds are aloof or suspicious of strangers, etc. These intergroup similarities do not make the breeds interchangeable, however; a prospective buyer should also feel an emotional connection with the specific look, attitude, history, or character of the breed when making a choice.

Like the dogs they raise, purebred breeders are not interchangeable. Some work to improve breed health by using genetic screening before breeding to avoid potential structural or organic problems in the puppies. Some raise puppies in their homes, some keep them in kennels. Some begin housetraining and good manners lessons before puppies go to new homes. Most control parasites and keep up with worming and vaccinations. So, even with popular breeds (some would say especially with popular breeds), some research is necessary.

Just as there are many breeds of dog, there are many types of breeders. Just as there are many breeds of dog, there are many types of breeders.

|

Casual breeders – those who breed their pets to get a puppy for themselves and sell the rest of the litter – often do little to assure the genetic health of their breeding female, may sell puppies younger than eight weeks of age, and may not offer a guarantee of any sort.

Show and performance dog breeders carefully match sire and dam for compatibility and breed for good health and breed-specific traits.

Working dog breeders also carefully match sire and dam and breed for good health, but they also test their breeding dogs for working ability according to the breed history and sell many puppies to working dog buyers. Because working dogs are likely to need a higher level of exercise and training and tend to focus intently on their jobs, they are generally not suitable as family pets.

Commercial breeders have gotten a bad rap in the last decade or so, but many run clean operations and pay adequate attention to dog health while raising dogs as a business. Many commercial breeders sell their puppies through pet stores; some sell directly to the public. The US Department of Agriculture and some states license and inspect commercial breeders.

Buyers looking for an older puppy or adult dog have several choices.

Some show, performance, and working dog breeders have dogs that are retired from their breeding or training programs and make them available to pet homes. Most national and many regional or local breed clubs have rescue programs for dogs that need a new home. Many of these groups have dogs that lost their original home because of illness or death in their families, job loss, divorce, or other life change. Dogs from breeders and breed rescues are generally healthy, have good manners, and are socialized and matched with the adopting family.

A few shelters or unaffiliated rescues occasionally have purebreds for adoption. Buyers should be aware that these organizations usually have little or no information about the temperament or health of any purebred dog in their possession.

While commercial kennels and some show, performance, and working dog breeders face federal or state regulations and inspections, most rescues and non-government shelters escape official scrutiny unless someone files a complaint. This gap has led to a rise in retail rescues, organizations and small groups that transport dogs from areas that have lots of puppies and small dogs to areas where there is a shortage. Some states require rescues to register and provide proof that the incoming dogs are vaccinated and wormed, but the vast majority do not regulate such dog trafficking.

Activists promoting retail rescue conduct anti-breeding crusades and plead for families to “adopt, not shop” for a family pet. In some areas, they also campaign against the sale of puppies in pet stores – unless the puppies come from shelters or rescue groups.

Mixed breed dog (cross). Mixed breed dog (cross).

|

Mixed breed dogs are available from families who neglected to either manage or sterilize their pets and from breeders who deliberately cross certain breeds and use cute names (i.e., goldendoodles, puggles, cockerpoos, etc.) as a marketing tool, and shelters.

Some mixed breed dogs have purebred parents of different breeds, and some are the result of generations of crossbreeding. While many of these dogs become top-notch family pets, most of them have no known health or temperament history. This is especially true of dogs collected from foreign countries, off-shore territories, overcrowded US shelters, and in the aftermath of natural disasters and transported to various US destinations to find homes.

The US, Canada, Great Britain, and other western countries are also dealing with an influx of stray mixed-ancestry dogs from countries where free-roaming dogs are a problem and a charity arranges transport.

Although many dogs look like a particular breed, breeders must prove that their puppies come from purebred parents of the same breed in order to participate in dog shows and events and to register their litters. In the US, the American Kennel Club and the United Kennel Club both register dogs of proven parentage and ancestry. To register a litter, these registries require that the owners of the sire and dam report the breeding and describe the number, sex, and colors of the puppies. Each litter gets a number, and the breeder or owner then registers each puppy individually. Dogs must also have a tattoo or microchip identification, and, in some circumstances, the sire must have a DNA profile to verify parentage.

Most countries have similar registries to keep track of dog breeds and maintain breed purity, and many of these registries have reciprocal agreements so that a dog registered in one can be registered in another. This agreement aids breeders in adding new blood to their breeding programs.

AKC and UKC also sanction dog shows and skill events for purebred dogs and allow mixed breed dogs to compete in some general skill competitions such as obedience and agility trials. The proficiency events include breed-specific trials for herding dogs, hounds, bird dogs, and terriers and general events that showcase obedience, agility, and tracking ability. Some breed clubs also offer breed-specific tests such as water rescue (Newfoundlands), sledding (Samoyed), carting (Newfoundland, Rottweiler and Bernese Mountain Dogs),

AKC has about 500 member clubs (mostly breed clubs, kennel clubs, and obedience clubs), and hundreds more regional and local organizations that host events and seminars and conduct training classes. UKC is smaller with a few breed clubs and a scattered number of clubs that host events.

Along with its registration database, AKC has many programs that honor dogs, promote responsible dog ownership, and encourage fun activities with pets and show dogs, including the prestigious national invitational competitions, annual “Meet the Breed” celebrations, annual awards for service dogs, a comprehensive Canine Good Citizen program, and thousands of local and regional events. It also works through the AKC Canine Health Foundation to support research into canine diseases and spawned AKC Reunite, a national dog identification database to recover lost dogs.

The purpose of dog shows such as Westminster Kennel Club’s February extravaganza is to evaluate potential breeding stock. At Westminster and hundreds of other breed and all-breed shows, judges compare each breed to a written standard of excellence both by a hands-on exam and by watching the dog move. The standard for each breed describes its size, attitude, coat type, movement, and structure and notes any disqualifying faults.

Each show features classes for males and females divided into puppy and adult sections; judges select the best male and the best female to award points and then awards best of breed to go on in competition.

The origin of the dog and its co-evolution with human advancement is an awesome journey that is wonderful to contemplate, but it sheds little light on the breadth and depth of the human-canine relationship in the 21st Century.

For the past several decades and most especially in the 21st Century, the relationship between people and their dogs has been enhanced by sports for pets and breeding dogs, including obedience, agility, and tracking tests and trials and by opportunities to for dogs to serve as therapy or service animals, search and rescue workers, and medical alert dogs. Dogs are working members of homeland security agencies, police and fire departments, and military installations. They sniff for contraband and guard borders.

Both UKC and AKC offer sporting events. Obedience clubs have volunteer instructors who are adept at various sports and help students and their dogs compete for ribbons and titles. The registries keep records of achievements and awards titles when a dog has achieved three qualifying scores at a particular skill level.

Both UKC and AKC offer sporting events like agility. Both UKC and AKC offer sporting events like agility.

|

Dog sports include

Obedience, a set of exercises at three skill levels that progress from heeling on and off leash, a stand for examination, a recall, and the ability to stay in place in a line of other dogs to retrieving, jumping on command, locating an article touched by the handler, completing a signal exercise, and doing a drop on the recall.

Agility is a fast-moving competition for dogs and handlers who navigate a course of obstacles. Courses vary according to level.

Rally takes the course and timing aspects of agility and blends them with obedience exercises. Here dogs and handlers navigate a course of stations and complete instructions on a sign at each station. Dogs are off leash at the higher levels.

Dog can also compete in tests and trials that mimic their original jobs. AKC and UKC set the rules and award the titles for some of these events and breed clubs set the rules and award the titles for carting, water work, sledding, weight pull and other activities depending on the breed background.

Some independent groups also organize dog sports that may or may not be sanctioned by the big registries or purebred clubs. For example, AKC recognizes titles earned in Barn Hunt, a new sport that tests a dog’s ability to find a rat in a maze of straw bales but does not offer these trials through its event program.

Dogs and their handlers also use their superior senses to perform dozens of jobs from aiding handicapped owners to sniffing for arson clues, chasing criminals, searching for lost children, finding contraband at airports, guarding military installations, searching for mines and bombs, and checking for illegal drugs.

Some dogs still herd sheep or guard livestock on farms; some accompany hunters in the field to find and retrieve game; and some dogs track and kill rats in city alleys. Dogs are even involved in a project to protect cheetahs in Africa by guarding livestock from the big cats and thereby reducing conflicts with farmers.

A Gathering of Canine Good Citizens. A Gathering of Canine Good Citizens.

|

The vast majority of dog owners have no desire to compete in sports or train their pets for therapy visits, but they are interested in well-behaved dogs that don’t disturb the neighbors and can accompany families on walks, visits, and vacations. In the old days, owners had to wait until their pups were six months old to attend a basic obedience class, but today experts recognize that early training is better. So training clubs and businesses offer puppy classes for socialization and basic good manners work and AKC designed a range of certifications under the Canine Good Citizen Program for dogs of all ages. CGC begins with the STAR Puppy program, proceeds to the Canine Good Citizen certification and on to an advanced program called Community Canine. Last but not least is the Urban Canine program where city dogs learn to ride in elevators, walk along crowded sidewalks, and remain calm in city noises and hustle and bustle. The dog must pass each of 10 exercises at each level. Any dog, purebred or mixed, can take a CGC class or test as long as it is registered or enrolled in AKC’s registry.

Just before the dawn of the 21st Century, and after a hiatus that lasted decades, states, cities, counties, and other jurisdictions began to enact a broad spectrum of rules restricting dog ownership. The result: In a nation of dog lovers, a growing body of laws and regulations limit or prohibit ownership of certain breeds or types of dogs; tax the ownership of intact dogs and dog breeding; set standards for dog care in kennels; specify the type of fence (or prohibit fencing altogether) a property owner can have; ban or limit the use of tethers; and bar the use of husbandry practices such as tail docking, ear cropping, and bark softening.

Ignorance definitely isn’t bliss; what you don’t know about dog laws, policies, and regulations can disrupt your world.

These laws generally fall into four categories:

Zoning codes may limit the number of dogs in a household or prohibit puppy sales. Zoning codes may limit the number of dogs in a household or prohibit puppy sales.

|

Pet owners may also face constraints imposed on residential developments directed by an association of property owners. These constraints are often included in the policy manuals given to new residents and can include limits on the size or weight of the dog, guidelines for fences, curbs on dog houses or exercise pens, and breed bans. They are not laws but matters of contracts between residents and the managing board.

These are the shoals and reefs that await dog owners throughout the country. It’s no longer enough to take good care of pets and kennel dogs, it is necessary to beware of lawmakers, do-gooders, and radical activists who insist that their way is the only correct way to do the job. So some navigation hints from NAIA:

Thorns may hurt you, men desert you, sunlight turn to fog; but you’re never friendless ever, if you have a dog. —Douglas Mallocker Thorns may hurt you, men desert you, sunlight turn to fog; but you’re never friendless ever, if you have a dog. —Douglas Mallocker

|

Discover Animals is a web-based educational resource offered by the NAIA

Discover Animals is a web-based educational resource offered by the NAIA